We are accustomed to Advent. It is the season that is all too familiar to us. It is of course the forerunner of Christmas in our minds. It conjures up holiday images of thanksgiving of, giftgiving, of togetherness, family, and blessedness. We are used to thinking of Advent in this way. It is the time for Christmas carols, for Christmas decorations, for good cheer and good food.

All this might be well and good. But it truly has nothing to do with the meaning of Advent. For Advent is about expectation. Advent is about a coming. Advent is about a life lived in a sort of nonsensical hopefulness, an irrational expectancy in the face of uncertainty, fear, and death. Advent is about longing. As our prophetic text has it today: “Oh that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence!”

You see, before Advent leads to Christmas, before expectancy and longing for liberation lead to new creation, before all these there is uncertainty, doubt, forlornness, sorrow, despair. The season of Advent calls us out of our rush to Christmastime sentimentality. It tells us to tarry with the unfinished nature of our lives. It asks us to take the time to grieve and to cry out. It refuses to prematurely suture our wounds. The demands that our hope be a deep hope, one that goes all the way down to the root. It calls us away from shallowness, from easy hopes for small transformations, for manageable, spiritual, little victories.

The longings of the prophets were deep longings. They were longings for a total liberation, for the thoroughgoing transformation of the world into the dwelling place of God. Likewise the hope of the people of Israel at the time of the birth of Christ was a deep, desperate hope. It was a hope for tangible deliverance from tangible slavery and suffering. It was a hope for real and true freedom from real and enslaving forces of domination. It was not a quaint spiritual hope for a spiritual savior to take care of our spiritual problems and help us in our generally good lives.

No, at the root of our faith at the root of our confession that our Lord and Savior was born of the Virgin Mary as a baby, lies deep apocalyptic expectation. An abiding call for a climactic transformation of all that is into something new.

The scandal of Advent lies inside this mystery, the mystery of a child in whom this apocalyptic transformation of the world waits to come about. Behind the manifest weakness of the newborn Jesus lies the manifestation of the New World order that is coming from God. All this must begin with the real, raw, and uncertain hopes that this broken world demands of us. We must begin where we are, in the midst of sorrow and suffering, uncertainty and incompleteness. It is from here that we must cry out for liberation. And it is from here that we must learn to recognize the surprising way God will surely answer us with salvation. And truly it is this surprising act of God to save us that we truly long for, as the prophet speaks of: “awesome deeds that we did not expect”!

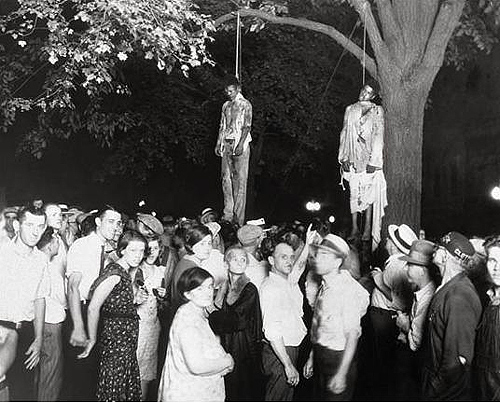

Amidst the failures of human projects and power, politics and procedures, the hope of Advent comes alive as true longing, longing for fundamental change and transformation of the world. Amidst the wreckage of the earth, from the edges and corners of this ravaged world comes the hope of Advent. The hope for the tearing open of heaven and the shaking of the mountains, the hope for the upending of every status quo, the defeat of all powers of domination. In the face of devastation and victimization comes the hope of Advent, the hope for a transformation and liberation that can barely be imagined, that can only hoped for, only be longed for — that only a decisive act from God alone can bring.

Advent is a time of apocalyptic longing, of sitting amidst the fragments of this world and the fragments of our lives and longing for a fundamental change in the face of it. It is a word that is always in season in the midst of our human games of power and politics, of idolatry and ideology. It is the same expectancy that runs through Yeats’ poem, “The Second Coming”, written in the wake of the devastation of WWI. Amidst the ruins of the optimism of the 19th century, the world was thrust into despair, and apocalyptic longing as the 20th century dawned in blood and destruction:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

The poem speaks of the incoherence and failure of the modern world amidst the destruction that humankind has brought down on itself. It looks to the world and sees a desolate place, a desert haunt in which bestial powers and darkness are the norm. And yet, precisely in this place, the place of incoherence and lost innocence, the place of desolation and destruction, the poet looks, longingly for a revelation, for the coming of something new, reminded of a rocking cradle that upended twenty centuries of stony sleep. Even as it looks for a rough beast, slouching towards Bethlehem to be born, for some strange new power to arise, it is this rocking cradle that haunts the poet’s memory. This unexpected gentleness and vulnerability that cannot be assimilated to the world of beasts and powers, of domination and subjugation.

So also did the prophet long for the climactic tearing open of the heavens, for the shaking of the mountains, and the overturning of the nations. And just so, in the face of the hope of Advent, God did truly come, and promises to come again. But this coming was not the one we envisioned. No, no. This above all was the awesome deed we did not expect: That the climactic, apocalyptic invasion of God to liberate and transfigure the world came, not in power as we know it, but in the form of the least of these, the most vulnerable of the world’s humanity. God’s coming, God’s faithfulness to come and save us, and come through on our every hope, our every longing, our every outcry was so strange to us, so unbelievably unexpected, that we humans would ultimately respond by rejecting it with crucifying malice.

But this is truly the grace, truly the word of hope on this side, between the Advents, that God’s coming to us, God’s fulfillment of the world’s hope did not come on our terms. The rocking cradle and the empty cross do indeed vex us to nightmare, and just so does the living Jesus and the empty tomb call us out of our nightmare-bound sleep and into new life, a life we could not have expected or imagined. And just so it calls us into new hope, a hope that realizes, in the face of God’s surprising coming to us, that our hope on our terms tends to lack imagination. God comes to meet our cries for the transformation of the world as a baby. And God comes to us when we have become crucifiers saying “Peace be with you. Do not fear!” This is the God who is coming to us. The God of the cradle and the cross. The God who saves us, not with power, but with the glorious powerlesness of unbounded, self-abandoning love.

So as we enter into the story of Jesus again, this new year, enter it as we must enter it if we are to be honest:

- Come with longing.

- Come with sorrow.

- Come with incompleteness.

- Come with failure.

- Come with depression.

- Come with anger.

- Come with despair.

- Come with uncertainty.

- Come afraid.

- Come vulnerable.

Come into God’s story where we are, in the midst of the flaming fragments of this world, crying out with all creation for newness. Do not shrink back from truly crying out, from truly longing, from feeling the depth of our need for transformation. And in that moment and in all the moments that follow after it, prepare yourselves to be surprised when God does come on the scene to save and to heal and to restore us. God is truly coming to us, but it may not be the coming we seek. It may come to us in the form of one of the least of these. Or in the form of a brother or sister, perhaps the one you don’t want to have it come from. Prepare yourself to be surprised by how and where and in whom God will come to you to call you back to the life of the kingdom.

But our great comfort, and our great hope, the hope that Advent also reminds us of is this: That even if God’s coming is not what we would expect, project, construct, or desire, it is coming nonetheless, and our ability to fail in recognizing it does not go as deep as far as God’s unfailing love, the love that will transform all things into life. The good news of Advent is that God is truly coming in Jesus and that this will truly surprise and shake us up into new life, no matter how much we may misunderstand or fail to see. This Advent give yourselves again to hope, and in hoping, give yourselves to receive God’s surprising, unexpected way of coming in response to our hope. For this indeed is our good news, that the kingdom of God will surprise us, will transform, and will go beyond our any of our wildest hopes.