I’ve always enjoyed the work of James Cone. Since reaching his Black Theology and Black Power, A Black Theology of Liberation, and most of all God of the Oppressed in my seminary days, I’ve always considered him a vital theological voice that “white Christians and their theologians” as Cone would say (i.e. me and most of the people I know) desperately need to really take the time to hear. His God of the Oppressed remains, I am convinced, one of the most important works in christology of the 20th century, and deserves far more attention than it gets.

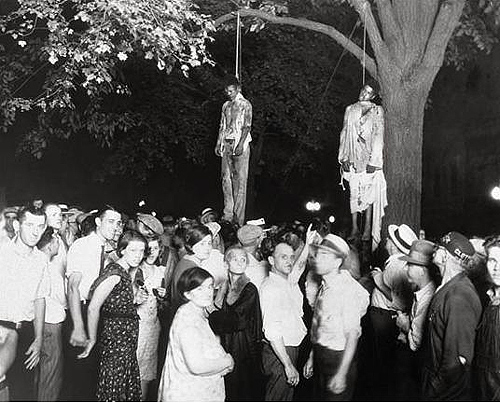

But having now finished his more recent work, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, I find myself stunned and shaken. Not because I didn’t know what Cone’s argument was before I began reading, and not that I didn’t know that I basically agreed with it already, which I did. (The argument in a nutshell: “The cross and the lynching tree interpret each other. . . . Can the cross redeem the lynching tree? Can the lynching tree liberate the cross and make it real in American history?” [p. 161]. Cone believes it can and powerfully shows why he does.)

No, the reason I find this work so shaking, so powerful is because it seems to be a work of memory that is truthful and profoundly hopeful at the same time. It dares to go all the way into the void and yet still call forth the transcendent hope of the transforming power of the Gospel to redeem the horrors and holocausts of history in their worst possible forms. And it doesn’t get much worse than the up close and frank stories of the lynched black bodies that are strewn across recent American history. His account the lynching of Mary Turner, a pregnant woman, wife to a lynched man named Hayes Turner will remain branded in my memory as one of the more horrifying stories I have ever read on a page (p. 120).

In the concluding section of the book, Cone really brings things together powerfully, in a way that frankly left me in awe (a rarity for conclusions of theological books). A few segments may help paint a picture:

As I see it, the lynching tree frees the cross from the false pieties of well-meaning Christians. When we see the crucifixion as a first-century lynching, we are confronted by the reenactment of Christ’s suffering n the blood-soaked history of African-Americans. Thus, the lynching tree reveals the true religious meaning of the cross for American Christians today. . . . Yet the lynching tree also needs the cross, without which it becomes simply an abomination. It is the cross that points in the direction of hope, the confidence that there is a dimension to life beyond the reach of the oppressor (p. 161-62).

What is so striking to me in Cone’s work here is the way in which faith is so palpably honest and real, clearly flowing from a life that has actually wrestled with the non-theoretical darkness and hopes for non-theoretical new life. This is a faith that is daring, a faith that screams “Why?” against oppression and slavery and cries “Hallelujah!” in hoping for a true transformation of life to come. This is a faith that actually looks for a transformation of victims and oppressors rather than simply an inversion of that diabolical relationship:

The cross of Jesus and the lynching tree of black victims are not literally the same—historically or theologically. Yet these two symbols or images are closely linked to Jesus’ spiritual meaning for black and white life together . . . Blacks and whites are bound together in Christ by their brutal and beautiful encounter in this land. Neither blacks nor whites can be understood without reference to the other because of their common religious heritage as well as their joint relationship to the lynching experience. What happened to blacks also happened to whites. When whites lynched blacks, they were literally and symbolically lynching themselves—their sons, daughters, cousins, mothers and fathers, and a host of other relatives. Whites may be bad brothers and sisters, murderers of their own black kin, but they are still our sisters and brothers. We are bound together in America by faith and tragedy. All the hatred we have expressed toward one another cannot destroy the profound mutual love and solidarity that flow deeply between us—a love that empowered blacks to open their arms to receive the many whites who were also empowered by the same love to risk their lives in the black struggle for freedom. No two people in America have had more violent and loving encounters than black and white people. We were made brothers and sisters by the blood of the lynching tree, the blood of sexual union, the blood of the cross of Jesus. No gulf between blacks and whites is too great to overcome, for our beauty is more enduring than our brutality. What God has joined together, no one can tear apart. (p. 165-66)

This, I think, is an authoritative word of a truthful faith. If James Cone can believe that, then I hope I can live towards the same daring faith, the same truthful memory. I hope we all can find our way towards it.